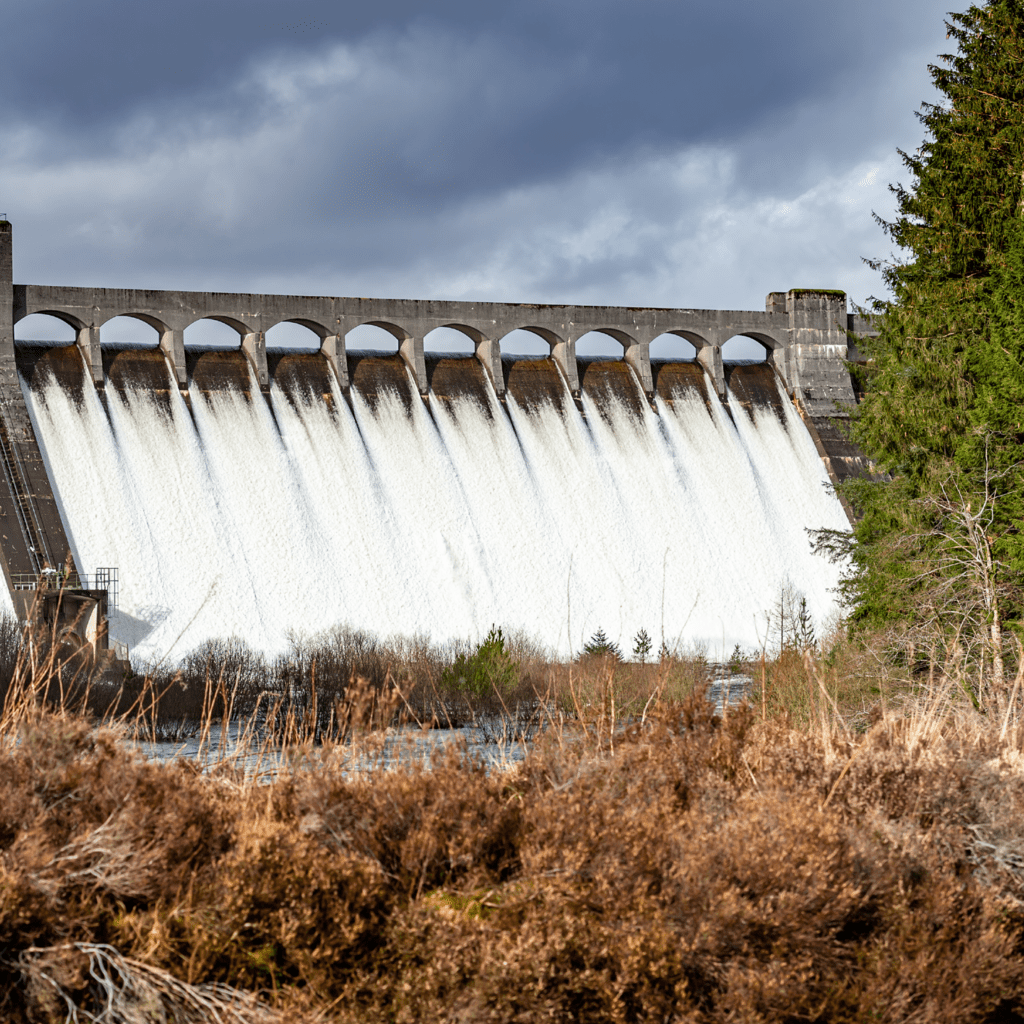

he banks and forests surrounding one of Scotland’s iconic lochs are to boost the fight against the climate crisis by becoming a carbon emissions sink.

Plans being developed by Forestry and Land Scotland (FLS) will see Scottish Water’s lands and catchment areas around Loch Katrine increasingly soak up emissions from human activity which cannot otherwise be eliminated.

The 8-miles long freshwater loch – which supplies water to 1.3 million people in much of the Greater Glasgow area and other parts of the Central Belt every day via infrastructure built by Victorian pioneers – is surrounded by 9000 hectares of land managed by Forestry and Land Scotland.

Together the two organisations are working to maximise the biodiversity benefits of around 5000 hectares – an area broadly equivalent to the size of the city of Dundee – to lock up greenhouse gases and ensure visitors and local communities can continue to enjoy the natural environment in the area.

A consultation is ongoing with local communities on future land management plans for Loch Katrine.

Using the environment to act as a natural sink for greenhouse gases on such a scale will play a vital role in achieving the net zero emissions targets set out by Scottish Water.

The public water and waste water organisation published its Net Zero Emissions Routemap in September 2020 and pledged to achieve net zero status by 2040 – but go beyond that by working with others to achieve similar gains.

Dr Mark Williams, Scottish Water’s sustainability and climate change manager, said: “Loch Katrine and its surrounding catchment is a jewel in Scotland’s natural environment crown.

People live, work and play there and it has an essential part in the daily lives of around a quarter of the Scottish population who receive their water supply from the loch.

“The surrounding woodland, rivers and landscapes not only shape the lives of thousands of people locally and further afield, but they are a become a vital component in our work to mitigate the impact of the climate crisis.

“We are working to reduce emissions across the whole network which produces 1.5 billion litres of water per day for customers and collects, cleans and recycles waste water, returning it to the environment. But some emissions simply cannot be prevented. Vibrant forests and peatlands act as a sink for them and lock them up stopping them emitting into the atmosphere.

“Smart approaches to peatland restoration, planting and re-planting, forest and land management, natural regeneration and biodiversity will mean Loch Katrine, for decades and longer to come, will be a valuable asset to our communities. We cannot plant our way out of the climate crisis. But biodiversity can help reduce the impact of activities on the very environment we rely on for our water.”

Making use of native tree species where possible will minimise ground disturbance and encourage natural colonization, with planting taking place where the seed source is scarce or where a greater mix of species is required.

This approach will blend with the work that FLS is already doing – such as the significant juniper planting in the extensive ancient woodland that rings the loch – and the ongoing management of the Ben A’an and Brenachoile Woods SSSI / Trossachs Woods SAC.

The project will also benefit the diversity of wildlife in the area, which includes badgers, bats, a huge variety of birds and particularly rare species, such as the Pearl Bordered Fritillary butterfly.

FLS’ Operations Forester for Loch Katrine, James Hand, said: “There is a huge variety of wildlife in the area and we’re currently carrying out a large survey to update our data on open habitats at Katrine to help inform our management decisions.

“We’ll be looking at how habitat enhancement can benefit the many species to be found here, also taking care to avoid planting in areas where it will be of detrimental impact on key species – such as Golden Eagle – and priority habitats such as peatland and upland heathland.

“This careful, considered approach will bring significant, long-term benefits for wildlife. It’s all about finding the right balance.”